Fanning the Flames

Flames! flames! terrible flames!

What a fearful destruction they bring.

What suf'fring and want in their train follow fast,

As forth on the streets homeless

thousands are cast,

But courage! courage! From the mid'st

of the furnace we sing.

George F. Root, Passing through the Fire

While eyewitnesses, journalists, and fire historians claimed to base their accounts on fidelity to fact, others took the great conflagration as an inspiration for flights of creativity and imagination. There was, to be sure, much inventive embellishment in the "truthful descriptions," but what might be called the literature and art of the fire more deliberately shaped Chicago's misfortune into aesthetic forms with a life of their own.

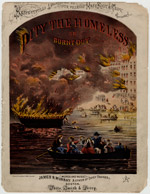

And there were plenty of such forms, all aimed at a broad audience. Poets of note, including John Greenleaf Whittier, Bret Harte, and Julia Moore, the death-and-disaster-fixated "Sweet Singer of Michigan," as well as songwriters like George F. Root, were among the many who set the conflagration to rhythm, rhyme, and melody. The Reverend E.P. Roe's Barriers Burned Away (1872), with sales of a million copies, was one of the most popular novels of the late-nineteenth century.

Meanwhile, visual artists were also busy at work. British painter Edward Armitage depicted Chicago as a naked and prostrate maiden receiving the tender mercies of two clothed female figures symbolizing England and America. Almost as spectacular as the fire itself was Isaac N. Reed's and Howard H. Gross's Fire Cyclorama, presented during the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in a specially constructed circular building on Michigan Avenue between Madison and Monroe streets. Upon entering this turn-of-the-century mammoth exercise in "virtual reality," one was surrounded by a 360-degree view of the destruction of Chicago that was fifty feet high and four-hundred feet in circumference.

Such dramatic re-creations hardly ended there. The fire provides the climax of the film In Old Chicago(1937), which gave a starring role to the special effects team. This motion picture takes numerous dramatic liberties, from small inaccuracies like showing firemen using manual pumps (by 1871 the city's equipment was powered by steam) to wholesale inventions like a stampede of stockyard cattle through the center of town that crushes the mustachioed villain. The 1950s CBS simulated news program You Are There, which was anchored by Walter Cronkite and "covered" momentous historical events by having actual correspondents interview actors in period costume, traveled back in time to 1871 Chicago. It supplemented its own "reporting" with footage from In Old Chicago. Similarly, as reenactments of battles and disasters became a regular attraction at world's fairs and amusement parks, Chicago was burned down again and again. The great fire was featured, for example, at White City, the park that operated from the turn of the century to the Depression at 63rd Street and South Park Avenue. In New York City's Freedomland, which had a short life in the early 1960s, a cast of firemen (again operating hand pumps) rushed several times a day to the rescue of a steel-and-asbestos mock-up of Chicago ablaze.

All of these capitalized on and reinforced the vivid public memory of the fire. Whether the conflagration was their main subject, or, as was the case in such fiction of the fire as Martha Lamb's Spicy (1873) and John McGovern's Daniel Trentworthy: A Tale of the Great Fire of Chicago (1889), it was deployed as a device to complicate or resolve (sometimes both) an already outlandish plot, the smoke and flame and terror and suffering guaranteed audience interest. More intriguing, however, are those works that, like the many sermons on Chicago's terrible ordeal, seized on the fire as text from which one could extract some higher meaning. And, also like these sermons, the meaning was almost always unashamedly sentimental and relentlessly moralistic.

This is especially true of the poetry, which talks of the fire in terms of pride and humbling, redemption and purification, courage and brotherhood, all within an explicitly evangelical framework. Whittier's poem, probably the best of what is even by forgiving standards a dismal lot, captures this spirit in the last three of its ten stanzas (several other fire poems droned on considerably longer):

How shrivelled in thy hot distress

The primal sin of selfishness!

How instant rose, to take thy part,

The angel in the human heart!

Ah! not in vain the flames that tossed

Above thy dreadful holocaust;

The Christ again has preached

through thee

The Gospel of Humanity!

Then lift once more thy towers on high,

And fret with spires the western sky,

To tell that God is yet with us,

And love is still miraculous!

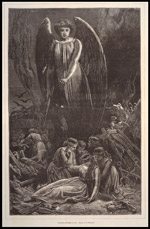

Not all of the art and literature of the fire is so reassuring, however. A drawing by illustrator Alfred Fredericks for an issue of Every Saturday is similar to Armitage's in that it shows several noble young women helping stricken Chicago to her feet. Frederick's work is more unsettling than Armitage's because some of these maidens of mercy are forced to fight off predatory hounds with savage fangs. This life-and-death drama is set against the backdrop of the ruined city, over which hovers an ominous winged female figure holding a torch, as large black birds circle in the sky. This scene suggests that while the forces of good will resurrect Chicago, they must always be on guard against the agents of chaos and darkness.

The fire fiction similarly conveys both positive and negative messages. The main story line of Barriers Burned Away is a conventional love plot drenched in Christian piety and democratic ideals. It would appear that protagonist Dennis Fleet's hopes to win the affections of Christine Ludolph, the beautiful but haughty daughter of a wealthy expatriate German baron and art dealer, are doomed. What stands between them are Christine's aristocratic arrogance and her cold-hearted atheism. In the crucible of the fire, however, she loses her father, her fortune, and, most important, her false beliefs. Joyfully declaring, "Every barrier is burned away," she pledges herself to Dennis, America, and Christ. But in the course of her swain's rescuing Christine from the physical dangers of the fire, he has to protect her at the point of a gun from the brutes and thugs that, like the savage dogs in Fredericks' drawing, menace the respectable refugees huddled along the lakefront.

For all their lofty symbolism, elevated language, and complexity of plot, these works are in some ways simpler versions of the eyewitness accounts and the media reports on the fire. Their authors seem even more determined to derive a few clear meanings from this overwhelming event, always with an emphasis on traditional values and social stability. But to demonstrate the power of the forces of faith and good, and to be sure of their own imaginative appeal to the popular imagination, the art and literature of the fire had to demonstrate how dire was this visitation that consumed Chicago. In so doing their authors revealed deeply felt concerns about the forces of destruction and disorder of which the fire was a more awesome symbol than any they could devise.